The inspiration for this blog post came from a conversation with a colleague who lamented the sheer number of meetings he now has to attend. As a recent promotee to team lead, his days are filled with managerial tasks, leaving less room for the technical work that once was his primary focus. This scenario is commonplace in large organizations where career advancement often equates to a transition into management. Such a shift means trading hands-on technical work for overseeing others, a change that isn’t always welcomed.

Many would view a promotion as a positive step, given elevated status it brings within a company, sometimes accompanied with higher salary. However, I’ve encountered several individuals who dread this transition, particularly those who relish the technical aspects of their roles.

The Case Against Becoming a Manager

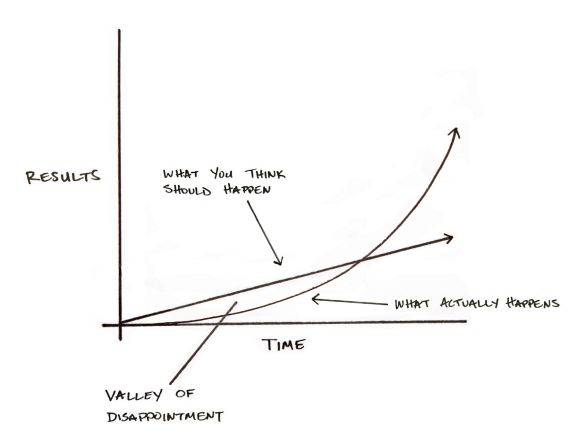

I firmly believe that highly skilled technical professionals should not automatically be funneled into management roles, nor should they be burdened with less critical tasks that divert their attention from their primary projects. My stance is supported by literature on productivity and focus, including concepts like flow state [1], Deep Work [2], and Hyperfocus [3]. Engaging in multiple, superficially handled projects is significantly less effective than dedicating oneself to a handful of technically demanding projects—ideally, one or two at a time. To understand why, let’s examine a graph from “Atomic Habits” that illustrates the relationship between effort and results over time.

Progress Is Never Linear

The common belief that progress is linear is a misconception. Many assume that a fixed unit input of time and effort yields a the fixed unit of results proportionally. Yet, the initial stages of any challenging project are typically slow due to the learning curve involved. Once we’ve assimilated the necessary information, our ability to generate solutions and ideas accelerates, thanks to reduced cognitive load thereafter. This phase of rapid productivity is often referred to as the flow state.

Achieving this accelerated productivity curve requires a significant upfront investment of time. Context-switching between multiple projects keeps us in a state of shallow productivity, as each switch requires time to recalibrate our focus and memory. Consequently, multitasking across various projects results in diminished overall progress compared to concentrating on a single project.

Practical Advice

For those already in management positions, mastering effective leadership is a distinct challenge, one that I hope to address in future blog posts. However, for technical professionals who thrive in their current roles, my advice is to resist the push towards management if you can get a salary boost without it. Prioritize projects that are complex and challenging, safeguarding your time to maintain deep focus and engagement. Protect your time, cherish the flow state!

Resources

[1] Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [2] Deep Work by Cal Newport [3] Hyperfocus by Chris Bailey [4] Atomic Habits by James Clear